Think Before You Buy: Ethics of Fashion Goes To Uighur For Sustainability with Amelia Pang

PAGE Magazine

By Chloe Konrad

I used to think “Made in America” labels were overrated. I’d always been told that outsourcing jobs and creating factories abroad is “good for the economy.” And of course, I believed it. Then I talked to Amelia Pang.

Pang grew up in the video store, one her parents owned actually. With hard-working immigrant parents who found themselves often quite busy, Pang kept herself company with the movies from the store and boxes and boxes of books from the local library.

On weekends, Pang went to Sunday school with other Chinese Americans in Laurel, Maryland. But in this place, a place where she should feel comfortable surrounded by others of similar culture and tradition, Pang always felt a bit out of place. At a young age, she began to notice differences between her and her friends at Sunday school.

“I just looked so different from them,” Pang said. “Everything from my skin color to my nose to my facial structure and the texture of my hair. Everything was really, really different from other East Asians and I never really quite understood why until fairly recently.”

But in 2012, Pang learned about an SOS letter from a labor camp. A woman in Oregon opened up a box of decorations from Kmart and instead of the retail therapy gratification we’re all so used to getting, out fell a letter from a labor worker in China. A little later on, Pang saw a picture in the news of the Uighur detainees in camps and began to realize how she was connected to them.

Pang immediately knew she needed to do something about it in the best way she knew how: storytelling. At this point, she was already a feature writer and investigative journalist and had received awards for her writing. But what Pang was set out to do would become her most important and cherished project yet.

“Over the years there’s been a lot of similar SOS letters being found … it always makes the news, makes the headlines, but nobody ever talked about how it arrived there,” Pang said.

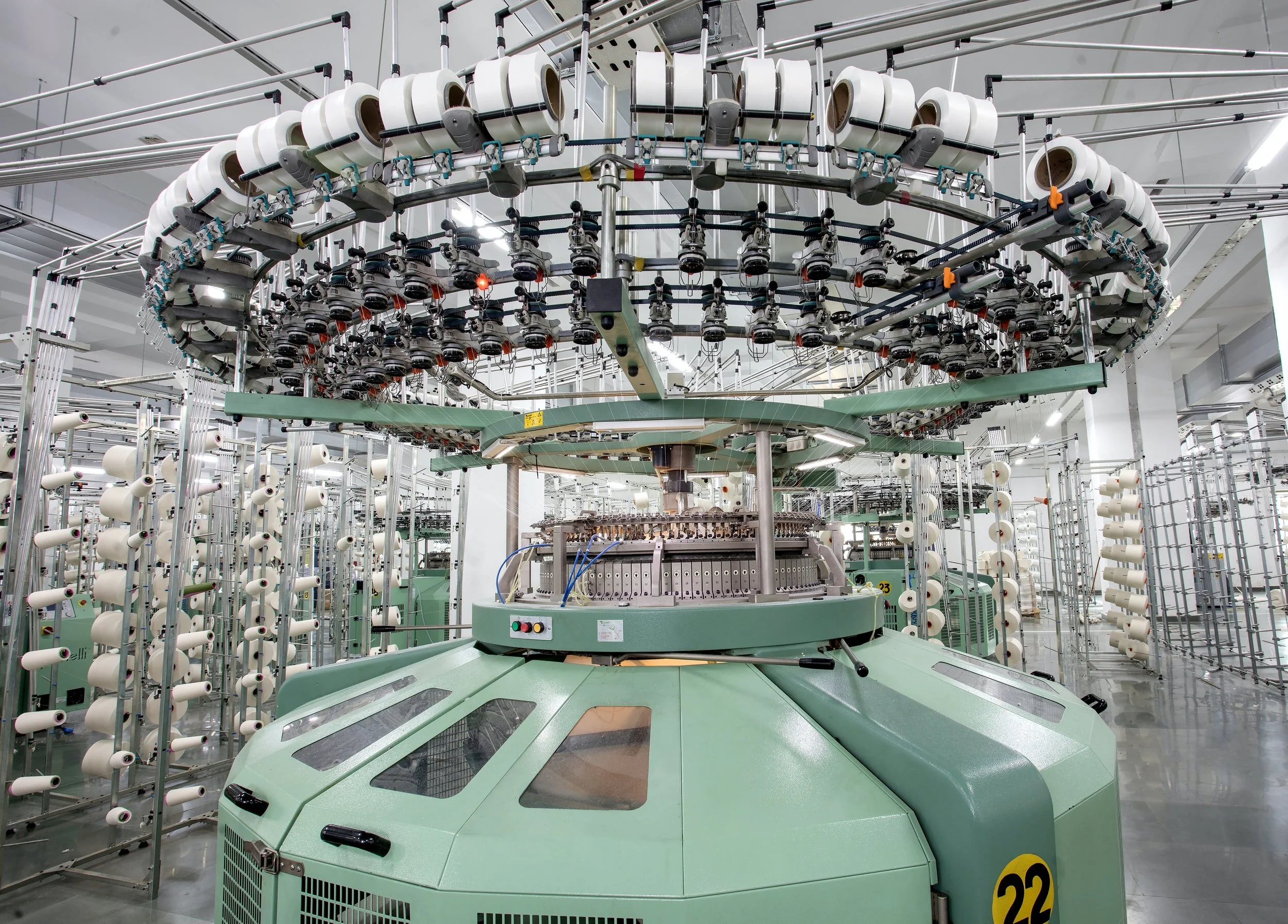

“How did something that was manufactured in a labor camp end up selling in our stores and entering our homes.”

Over about the next five years, Pang researched and wrote “Made in China.” The book found its way onto Newsweek’s most anticipated books for 2021 and was released February 2nd. Pang wanted to write about how our actions impact forced labor and how easy it is for companies to outsource. To do this, she posed as a businessperson and traveled to China to investigate the camps.

“I realized just how open the employees and guards at the camps were to talking about the forced labor that went on inside,”

Pang said.

“If you call these labor camps and say you’re from an overseas company that wants to source from them, they’ll say that’s absolutely fine and transfer you to their sales department.”

Most people can’t go on social media today without being bombarded with information about fast fashion and sustainability. But they all seem to be missing what Pang has been investigating: how ethical is fashion today? Gen-Z’s and Millennials are often credited with being the generations who might change everything. This gives Pang hope, but according to her, it isn’t just fast fashion that is causing pain for the Uighurs.

“I think fast fashion is definitely very problematic,” Pang said.

“Everybody claims to be transparent and sustainable. Every fast fashion company has a sustainability page … but it’s really not limited to fast fashion. I don’t know if there’s an industry that’s not impacted by this.”

Uighur forced labor camps have been found to be making PPE equipment since the start of the pandemic, they make hair extensions, even the raw materials in solar panels according to Pang. Even a product that says it is from India may have been made with raw materials from these camps. It’s easy to think that popular, wealthy companies might be excluded from this problem, but even Nike and Apple have been lobbying against the Uighur Forced Labor Prevention Act currently under dispute in Washington D.C.

Without action soon from international governments, there is legitimate concern for what might happen to the Uighurs in China. Pang cites researcher Rian Thum’s work as a good resource for more information on the possible escalation of this problem.

“He’s the one who said that he’s nervous that the next step for the Uighurs might just be mass extermination,”

Pang said.

“I know a lot of people are hesitant to say that … but I guess there’s not much stopping China from doing that … There’s so little action from the international community.”

According to Pang, our individual shopping habits and decisions impact this problem. The fast rate at which trends change and the expectation of cheaper clothing is forcing companies to look for alternative ways to produce. Pang says changes in these behaviors can have a large impact.

“They can’t realistically make any money and so they have no choice but to outsource work,” Pang said. “If we stop rewarding companies for constantly offering the lowest prices and the latest trends so immediately, we can really remove some of the huge factors that compel factories to outsource work to forced laborers.”

“They can’t realistically make any money and so they have no choice but to outsource work,” Pang said. “If we stop rewarding companies for constantly offering the lowest prices and the latest trends so immediately, we can really remove some of the huge factors that compel factories to outsource work to forced laborers.”

Featured

Tap to read…